The grandest, greatest, most pervasive mystery we face is the big “what happens after we die.” Entire faith systems, rituals, and cultures have evolved from this question because, we, the self-aware, sentient beings that we are, are able to take a step back and wonder.

And worry.

In American culture, generally, we tend to cope with this question by avoiding the discussion of dying. We know about birthin’ babies. We know about healthy (and unhealthy) lifestyle choices. We know to go to the doctor and how often and when (whether we do or not and the why of these choices, that’s a different discussion).

But dying?

We don’t talk about it.

The first thing I wind up doing when I assume care for a person and their family is educating them on the dying process. So I thought I’d capture it here.

First thing first. Dying is a natural process. Our bodies know what to do. Barring trauma, such as a car accident, we all die pretty much the same way, regardless of the terminal disease taking our life.

Dying happens when our bodies can no longer maintain something called homeostasis, a balance between the many different needs and systems that keeps us up and running and able to hit the snooze bar in the morning. When a serious illness arises, the body compensates for the lack of support in that area. When an illness becomes terminal, the parts of the body that had been healthy and working overtime to pitch in are breaking down. It can get complicated. There may be multiple disease processes happening at the same time. Sometimes there isn’t any one terminal diagnosis, but there is enough disease in various body systems that, when taken together, the body is unable to thrive. To compensate.

Dying is failure to compensate.

When we know that a person has a terminal diagnosis that no longer can be helped with curative treatment, that’s when hospice begins. The focus shifts from curative to palliative. Medicine can no longer fix or address the cause. Medicine now attends to the symptoms and ensuring that the person remains as comfortable as humanely possible.

The course is different, but there’s a certain point where dying begins to look more or less the same. In hospice, it’s called “transition”. If the person is still awake, it can observed as a withdrawal of attention, a more internal focus. The person might start plucking at her clothes or sheets, what we call “picking”. Hallucinations can occur, secondary to lack of oxygen reaching the brain and acid-base imbalance as well as electrolyte imbalances. They grow more lethargic, their appetite diminishes or disappears entirely. They can can feel euphoric or spacey or confused.

At some point, the person goes to sleep. They become minimally to nonresponsive. Every time.

As the dying process becomes active, the brain hoards the blood for the vital organs, the heart and lungs. Typically, I’ve seen people go one of two ways at this point. Some will experience cold extremities as a result of the blood being preserved for the heart and lungs, and what looks like bruising – called mottling – as a result where the blood in the limbs pools. Some will spike a fever that can go quite high and they’re bodies stay nice and warm as a result. I have yet to decide if one way is better than the other.

Urinary output is scant to none. Bowel movements may still occur as we continue to break down cell material to the very end.

Probably the most notable change, other than the change in consciousness, is that the person’s breathing changes. The swallowing reflex disappears and saliva can and often does pool in the throat. This can cause a gurgling sound as air moves through the fluid, and can be disturbing for family members to hear. The breathing itself grows more rapid and shallow, can change to rapid and deep, then stop for a period of time before resuming. This is called Cheyne-Stokes breathing.

The heart rate becomes rapid, and often irregular, the blood pressure falls, and at some point, the heart and the lungs, they stop. And the person dies.

So, knowing this, where does hospice come in?

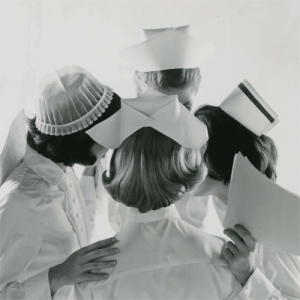

For however long the person is on hospice, from the moment they know they have a disease for which there is no longer any curative treatment wanted and/or available, we take over medical care in the home. We coordinate with the person’s primary care physician if desired, our hospice physicians, facility caregivers if appropriate, the family and the patient. The person’s goals become our goals. We continue to palliate and manage whatever medical issues the person has while keeping them as comfortable as possible and fostering independence and quality of life with what life remains.

We provide emotional, mental and spiritual support for not just the person, but the person’s family. We teach them what to expect. We answer a lot of questions and ask for more. We can’t fix a lifetime of patterns when they show up, but we can and do get people into the same room so that they can communicate.

When transition occurs, we watch and wait for pain, for anxiety. We look for issues with respiratory distress and air hunger. We palliate these and the gurgling with medications and at that point, all other medications that remain are usually discontinued.

The first drug is morphine. We administer it in liquid form and it’s given orally, absorbed via the mucus membranes of the mouth. Morphine serves two purposes: pain management and palliating respiratory distress. Most people are familiar with the former, many are surprised at the latter. Morphine acts on the respiratory center of the brain, reducing the respiratory drive and slowing those rapid respirations that often occur at the end. Morphine is also a vasodilator, meaning it opens up the blood vessels, allowing blood to flow more easily and reducing the workload of the heart, allowing it to slow down.

The next drug is lorazepam (aka Ativan). It’s given in tablet form that dissolves in the mouth, again absorbed by the mucus membranes. This is a benzodiazepene and used most often as an anxiolytic. It also helps with the sensation of air hunger, or shortness of breath, by relaxing the person. We give this to palliate the stress the body is feeling as it starts to truly decompensate.

The last drug is atropine drops. This is a medication more commonly known as an eye drop. At end of life, it’s given as drops under the tongue to dry up the saliva that pools in the throat and reduce the gurgling sound.

When a person is no longer able to speak for herself, it’s up to the nurse – and the family – to gauge discomfort and pain by non-verbal signs. The nurse educates the family if appropriate. The medications are titrated to comfort. We may also use oxygen, and we may give Tylenol as a suppository if they spike a fever (it’s uncomfortable to feel too warm).

Non medicinal interventions are used. A fan blowing across a person’s face can reduce the sensation of shortness of breath. Cool cloths on the forehead, blankets over the hands and feet. Music, the sounds and conversation of familiar voices – it’s presumed that hearing is the one sense preserved to the end.

The goal is a natural death, a comfortable, natural death.

The family’s role is to keep vigil. To watch and wait and pay witness, to be alert for pain or discomfort and get help when necessary. I’ve seen solemn families, I’ve seen laughing families, I’ve seen one daughter who turned her mother’s death into a celebration, setting up a butterfly altar on her overbed tray and calling out, “Look! There she goes!” when the moment came.

If I – we – do our jobs right, there is no mystery about dying by the time the person is in thick of it. The family knows what to expect, they’re prepared, and some times, they even celebrate the passing.

What comes next, though… who knows?